Place-based approaches - economic and social value

Engaging communities in the right way can improve economic resilience, lives and the environment.

Summary: Retrofitting can improve the operational efficiency and emissions profile of existing buildings and infrastructure. However, the approach to funding and implementation will depend on the kind of infrastructure, the owner / user and the location. In some situations, a place-based approach is needed to ensure buy-in, engagement and appropriate delivery of social value, economic and environmental benefits in a sustainable way for individual residents, communities and the various funders. This blog features a guest author - Rufus Grantham, co-founder of Living Places.

Why this is important: Communities are important stakeholders for almost every business. As a sustainability professional, understanding the nuances of engagements such as a place-based approach will be helpful in designing appropriate strategies.

The big theme: The built environment, encompassing residential and commercial buildings, communal areas such as parks, and supporting infrastructure such as energy networks, mobility, and water supply, is an important sustainability theme. It is an integral part of societal existence and a major resource consumption problem (40% of global raw materials) and decarbonisation problem (as much as 40% of energy-related GHG emissions) that needs investor, government, business and consumer attention.

The details

In a previous deep dive blog we discussed how there are a number of ways in which existing structures can be repurposed when they reach the end of their useful operational life. Indeed even while they are operational, their overall efficiency can be improved to improve their sustainability. This can involve retrofitting more modern, low carbon, energy efficient technologies and features or even reusing materials and elements from existing structures that have themselves come to the end of their lives. There are strong financial arguments in terms of longer term value creation. You can read that blog here 👇🏾

The appropriate funding structure for such retrofits is dependent on the type of project. It could be very different for residential, mixed use and large scale non-residential with each having different challenges for individual users and broader community considerations.

For some projects including community-based infrastructure, rather than an individual approach, a 'place-based' approach may be more appropriate.

At the heart of place-based impact investing is addressing the needs of specific places, to enhance local economic resilience, prosperity and sustainable development. As Jamie Broderick, Deputy Chair of the Impact Investing Institute commented:

"But to do that effectively, you need to engage with those communities. That is a process that is familiar to local government and the social sector, but not so much to asset managers."

The Impact Investing Institute has developed a guide specifically for institutional investors seeking to incorporate communities into the design and delivery of their place-based impact investments. The guide, "Fostering Impact: an investor guide for engaging communities in place-based impact investing" was developed with Involve, the UK’s leading public participation charity, and funded by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport.

Page 51 of the guide includes a one-pager practical checklist for asset managers, summarising the key steps in planning, delivering and sustaining community engagement, as well as key questions that investors should ask themselves at each stage of the process.

But what about individual residents?

Key considerations for individual residents are disruption and cost. The costs for individual residents to transition their properties to lower harmful emissions and lower annual running costs may have too long a payback period (40 years plus for significant retrofit), particularly where the average owner occupier in the UK, for example, is in their fifties. Now it does depend on how ambitious a retrofit you do. You can get a shorter payback if you just cherry pick the decent returning components but you won't end up with a deep retrofit and will not see the full potential benefits.

Living Places is a specialist not-for-profit organisation with diverse expertise that designs and advises on the implementation and funding for the place-based approach.

They believe the net zero transition can be delivered at pace, will make people better off, and will create healthy and resilient neighbourhoods across the whole country.

They do this by bringing together communities, local and national government, business, institutional fund managers and charities to collaborate on whole neighbourhood scale projects.

Nearly all of the blog from here onwards comes from Rufus Grantham, co-founder of Living Places. Rufus is passionate about the built environment transition and in particular how neighbourhoods can build resilience and sustainability. He and the Living Places team believe that a place-based approach can engage individuals and whole communities with a goal of improving lives whilst simultaneously benefiting the broader environment.

So we shall leave you in Rufus's excellent hands and come back with a conclusion at the end.

Living Places: delivering social, environmental and economic benefits through transition of place

Living Places was set up because, while place-based models are more complex to design and implement, we believe this approach has far more potential than current approaches to overcome barriers, scale action, minimise the cost to individuals and the taxpayer, and maximise the benefits realised and their influence on funding decisions. Here we explain why we believe that, what a place based model actually involves, and how it could be developed in any given national market.

Why explore place-based models?

Decarbonising the built environment is a necessary step to achieve net zero goals. But more importantly a decarbonised housing sector is also a cheaper to operate, more comfortable, and healthier housing sector with demonstrable economic and social value beyond carbon reduction.

The "received-wisdom" funding model to encourage the decarbonisation of buildings is focused on financial debt products for individual building owners to borrow money to undertake the work in isolation, complemented by a range of often time-limited, technology-specific subsidies. This approach is deceptively attractive because it is a market-led approach which is incremental to existing products and methods and therefore feels simple to implement. It is also an approach which is demonstrably not working.

To answer why we should look at place-based approaches, we first have to consider why the market-led approach isn’t working. What are the barriers?

The biggest single barrier is that building owners and residents simply don’t want to do it. There are a number of reasons for this.

- Affordability. It costs a lot up front to decarbonise a building and most people don’t have access to that capital

- Complexity. Even if the capital is available, choosing the right mix of technologies for a specific building is complex to ensure that the end result isn’t poor in terms of heat delivery, condensation, air quality etc. Most people don’t have the time to become experts

- Disruption. Even if the money is there and the right project can be designed, actually going through with it is disruptive. This involves often fairly major works to people’s homes, potentially even requiring temporary relocation. That isn’t attractive.

- Perceived Benefit. If you can get through the first 3 barriers, the reality is that for the individual the reduction in the energy bill relative to the cost of achieving it represents a poor return or rather a return that you would have to accrue for many decades before it becomes financially attractive. Individually we aren’t long term enough to find that attractive, we might take 3-5 years of savings into account but not the 30 or 50 required. To put it more bluntly the annual mortgage cost to fund a deep energy renovation is likely to be at least double the saving on the energy bill, thereby carrying out the work is to propose impoverishment of the resident during a cost of living crisis.

Another potential financial benefit is an uplift in valuation of the property. This may be true when energy efficiency is a rare thing but will fall foul of a zero-sum game when widely adopted and would anyway exacerbate a growing crisis in the affordability of housing. Housing valuation hasn’t yet reflected the incremental investment required to achieve net zero. Energy renovation is about protecting against downside not uplifting valuation.

The other, often referenced, individual benefit from those who have gone through it, ie improved home living conditions, is an experiential benefit only realised after the work is done and so not a great driver of making the decision in the first place. The range of other social benefits of doing this work at scale, e.g. a healthier population, significant job creation are not strong individual motivators.

So, can a place-based model overcome these barriers? We believe yes.

- Affordability. The default funding option with our blended finance solution is that there is no requirement for owners/residents to fund the work or take on any debt, whether individual or property-linked. The affordability issue is removed completely for the community

- Complexity. In a place-based scheme a professional design service is brought in for the whole neighbourhood removing the need for individual owners/residents to become experts themselves also resulting in better integrated designs that provide much greater efficiencies and outcomes.

- Disruption. Deep energy renovation is disruptive. This can’t be avoided but there are some steps which could mitigate it to a degree and become possible in a place-based model. For example, setting up a temporary removal service for items stored in lofts while insulation is being installed, or organising pre-paid localised temporary relocation accommodation if vacating the property is unavoidable.

- Perceived Benefit. For the individual resident, we are now delivering a (smaller) energy bill reduction for no upfront investment, clearly financially attractive, as well as a healthier more comfortable home the benefits of which can be communicated clearly at a community scale, with the possibility of carrying out the work on a small number of homes early to act as an “energy renovation show home”. We are also unlocking additional investment into the neighbourhood, which the community can co-design, taking agency in local regeneration and, with the right design, long-term collective financial benefit.

For investors and government, we are bringing longer-term investment horizons to the energy savings maximising their fund-raising capability, while better harnessing the valuation of wider social and economic benefits. This will minimise the amount of public sector funding required (though it will still be required) and fundamentally creates a delivery mechanism to actually get work done.

What is a place-based model?

The Net Zero Neighbourhood model involves planning, and co-designing with the community, a series of interventions across a whole mixed tenure/mixed use neighbourhood (c. 1,000 properties) and then funding those through a public/outcome-buying/private blended finance stack at no upfront cost or debt obligation to the community supported by a collective pay-as-you-save mechanism.

Figure 1: Net Zero Neighbourhood Overview

Source: Living Places

The different funders receive a range of benefits that they care about.

- For the public sector the case can be made for a cost-effective delivery of a range of public sector goals around economic stimulus and healthcare in particular, as well as partial repayment through tax.

- Outcome Buying Capital references organisations who may have specific aligned goals, for example leveraging an energy renovation project to deliver sustainable urban drainage and reduce the operating (and reputational) costs to water utilities.

- Institutional finance refers to organisations who are looking for socially and environmentally impactful, long-term, stable-yielding, investments, i.e., pension funds and insurance investment management firms. An option for community co-investment could also be included.

Figure 2: Funders and Investment Cases

Source: Living Places

This creates a funding stack (where funds come from, what they pay for, what value they deliver) that makes overall economic sense and a much more attractive proposition to residents.

Figure 3: NZN Funding Stack

Source: Living Places

How can we test, iterate and prove out this approach?

We believe Local Authorities, supported by regional or national government, are critical stakeholders in progressing this approach, to convene and enable the community and expertise required to build local demonstrator projects. To make this as cost-effective and impactful as possible, a cohort of Local Authorities would build demonstrator projects in parallel with a collective group of technical assistance partners that can ensure standardisation, maximise learnings, reduce reinventions and inform policymakers rather than procuring advisory support bilaterally.

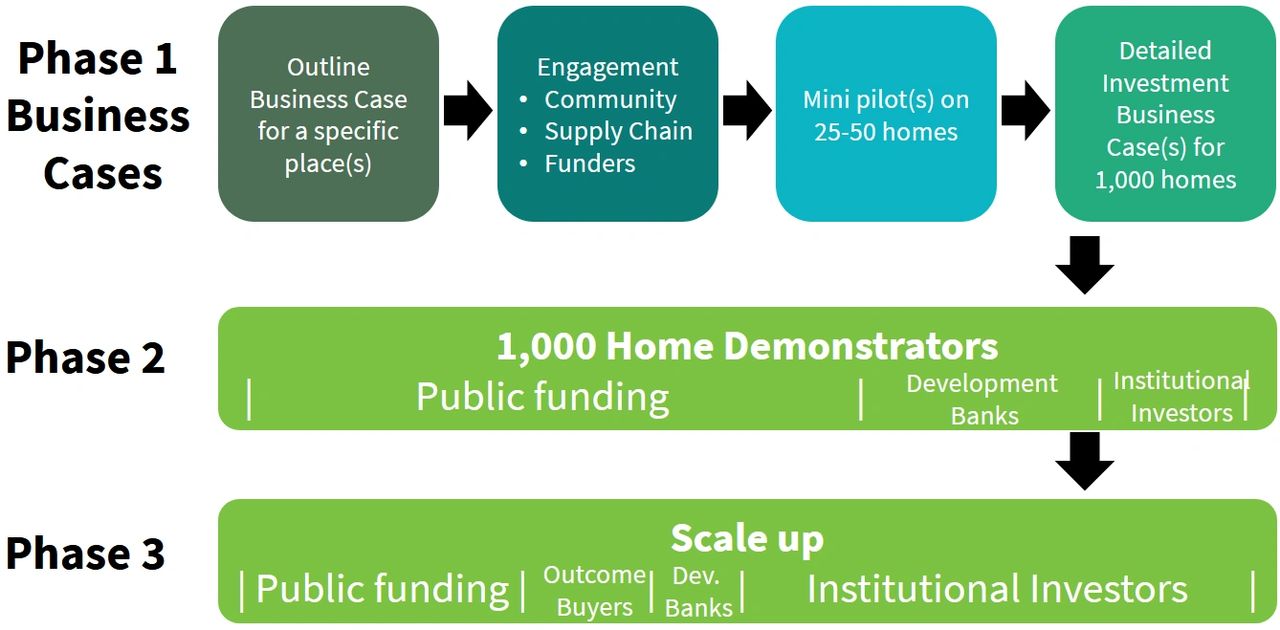

First, we will need to build the business case. That involves picking specific neighbourhoods, carrying out an initial assessment, based on the topology, building typology and community of what might be possible in terms of interventions. This will include a high-level financial assessment of likely costs and benefits that will form an Outline Business Case.

Figure 4: Key Business Case Tasks

Source: Living Places

The Outline Business Case forms the context to begin the engagement process with the community, local supply chain and funders to carry out a co-design process to deliver a better, more locally appropriate proposition and build enthusiasm and engagement in local residents and property owners.

We would suggest that ideally during this phase a small capital budget were made available to actually carry out energy renovation works on a handful of properties, to make the proposed bigger scale changes tangible to the community.

The engagement process would provide the detailed proposals and costings to build a Full Business Case that can then be put to the community for sign up and funders for capital provision as well as form the basis for supply chain procurement.

That will lead to funding of initial demonstrators, where lessons will be learned and applied to subsequent neighbourhoods. As the model matures and evolves the risk attached to it will reduce and the funding mix will shift from majority public sector to majority private sector.

Figure 5: Demonstrator Programme Structure

Source: Living Places

This approach will require funding, revenue most critically rather than capital, to create the capacity and capability to innovate, design, deliver and iterate these projects to build into city and national scale programmes. The most immediate pressing need is comprehensive funding for the Business Case Phase.

Figure 6: Business Case Funding Structure

Conclusion

Back to us at The Sustainable Investor. The built environment is a key focus area for decarbonisation. It is one of the biggest emitters when looking at both the embedded (creating buildings and infrastructure) and operational (running and operating) aspects. However, funding and implementation is very much dependent on the users and owners.

For individual residents and communities, affordability, complexity, disruption and the perceived benefit are critical in gaining acceptance. Done right and the lives of whole communities should be improved - and at a macro level contribute to reducing harmful emissions.

For the funders, the long payback period means that even in the impact world of 'willingness to pay' (the willingness to sacrifice some return for achieving social or environmental outcomes), careful consideration of the return profile is needed. And the overall funding could be comprised of stakeholders with varying needs including potentially investment from the community itself.

This is where a place-based approach can be hugely beneficial.

Expertise such as that from the Impact Investing Institute and Living Places can ultimately help bring social value, economic and environmental benefits in a sustainable way.

Guest author: Rufus Grantham

Rufus is the co-founder of Living Places, a mission-driven, social enterprise advancing the development, design, funding and delivery of community-focused, place-based models for a just, net zero transition.

Before co-founding Living Places in 2023, Rufus worked at Bankers without Boundaries (BwB), focused on built environment transition, conceiving of the Net Zero Neighbourhood (NZN) model and working with a range of collaboration partners and local and national public sector entities in the UK and across Europe to further develop it.

Rufus had a 23 year career in mainstream finance until 2019, is also co-founder of Mettle Capital, a data startup that uses machine reading to create ESG materiality and sentiment data on individual companies, and of hospitality operator BloodandSand.

Rufus's blog originally appeared as "Why should we tackle the complexity of placed-based approaches" on the Living Places website here, including a fuller definition of “Place-Based Transition.” Unless otherwise indicated, the views are those of Rufus Grantham and Living Places.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.