Sunday Brunch: Returning to burbing cows

We know that ruminants (mostly cows) are responsible for a big chunk of our methane emissions. As investors, who should we expect to act to reduce this, and how? And if it's not companies, should they still prepare for a lower meat/dairy future?

Sometimes companies need to prepare for a different future, even if their investors are not expecting them to fix the underlying climate related problem. Cattle (dairy and beef) related green house gas emissions are a good example. And what has happened to the alcohol industry could be a warning to investors.

And yes, this Sunday Brunch is a day late - moving house throws up all sorts of jobs that suddenly become urgent.

Let's run through the argument.

First up - cattle produce a lot of methane (hence the burbing cow reference in the title).

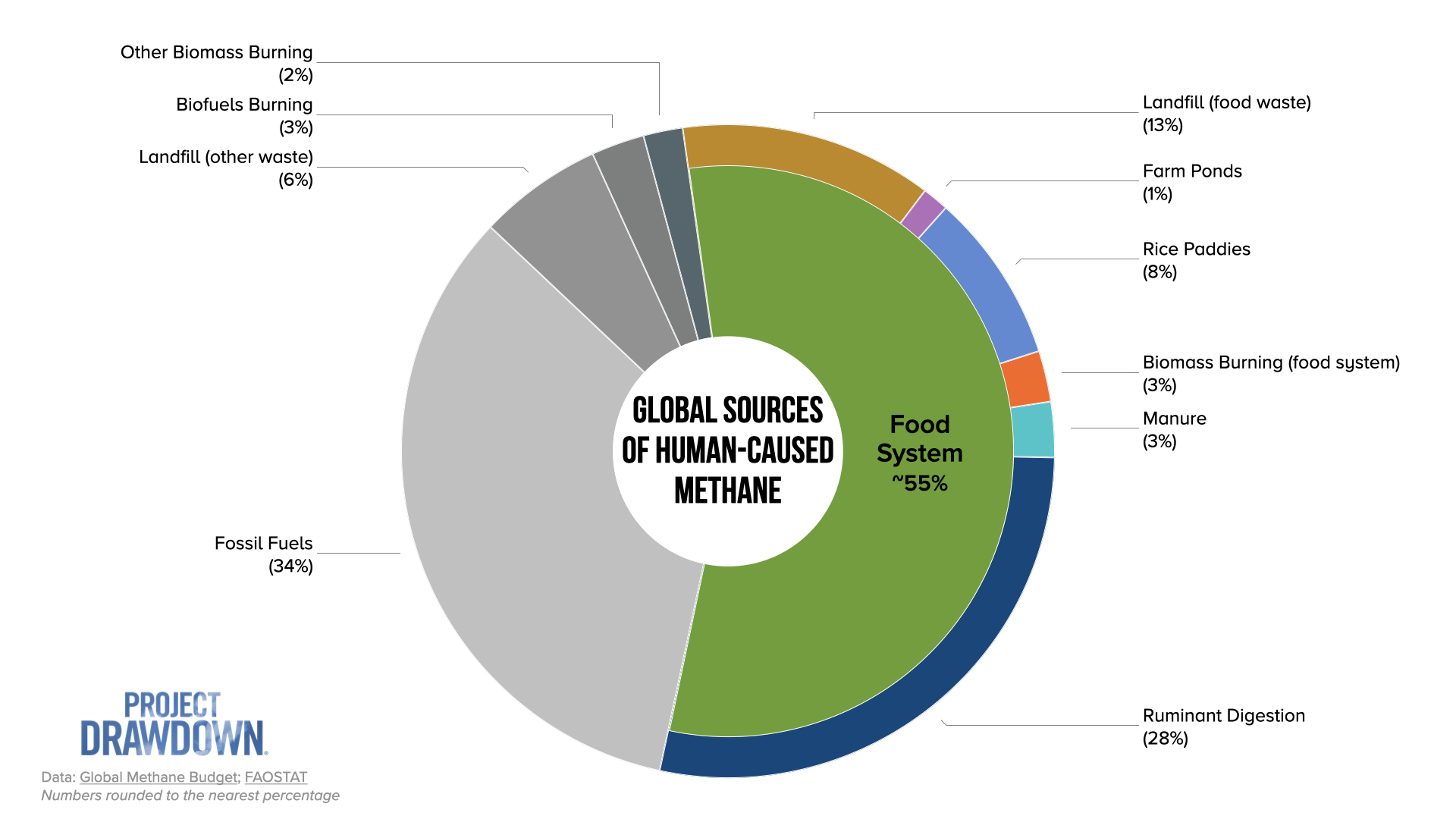

According to a recent report from Project Drawdown ...

There are a lot of cattle raised for beef and dairy on Earth – about 1.5 billion of them each year. And when they burp, they emit methane. Ruminant livestock (including cattle, sheep, and goats) with multi-chambered stomachs can digest grasses and other biomass that humans can’t. But this digestion process – and the belching that comes with it – emits about 28% of human-caused methane emissions.

And solutions that reduce this are challenging (although this may become easier over time). And as an investor it's hard to argue that this is a climate problem that companies can fix (on their own).

But equally, it's not enough for companies to say, 'there is nothing I should do'. Because other factors could come into play which would force their hand, and make adaptation to a different future required.

One obvious driver of change would be regulation, but it's not the only one. In fact we often argue that relying on regulation brings its own problems. Our experience is that very few politicians want to say outright that we have to consume less meat and dairy. And that they are going to push us that way via higher taxes.

The other driver of change is social preferences - basically consumers start buying different products. In this case less red meat and less dairy, or maybe versions that produce lower methane emissions.

You might think this second scenario seems unlikely, after all, why would consumers eat less meat and diary ? One answer might be price, but we also need to remember that consumer preferences change.

And when that happens demand for the product can fall (steadily if not rapidly), making the industry less profitable than before.

The push back I often hear to this argument in relation to meat/dairy is that outside of religious reasons, vegetarians are still a fairly small group. In the UK (just as an example) the Vegetarian Society claims that 4.5% of the population have a vegetarian or vegan diet.

But you don't have to be a vegetarian to eat less meat. According to an Oxford University study ..

'from 2008 to 2019, UK average meat consumption per capita per day decreased from 103·7 g to 86·3 g per day. '

That is quite a drop. And data from the UK Government Family Food report shows that this decline has continued. Plus, as the AHDB (the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board which represents farmers, growers and others in the supply chain) points out ...

'older demographics typically consume more beef and lamb, whereas younger consumers (aged up to 28) lean towards poultry'

So net net it's not unreasonable to think of this as a long term trend.

What can we learn from the spirits industry?

One other example of this long & steady decline in demand is what has happened in the alcoholic drinks industry. Demand has fallen and now, according to analysis by my old colleague Trevor Stirling (the highly experienced Bernstein Beverages analyst, recently reported in the FT), the companies now have really high levels of unsold stock (inventory). Which is causing investors to worry.

I used to be a beverages industry analyst (both buy & sell side) and back then we used to think of the industry as being both really defensive (ie predictable) and a good creator of financial value (solid sales growth and high ROCE).

It was true that demand for specific brands and spirits shifted over time. Vodka and then gin were for a time the spirits of choice. And a rule of thumb was that consumers would never drink the same spirit as their parents (maybe because it just wasn't cool). But steadily growing demand and price premiumisation (trading up) were seen as a long term trend.

There are all sorts of reasons why demand has fallen. It might just be the economy, in which case the decline may reverse. But it could also be more structural. Some analysts have pointed to the growing use of weight loss drugs (I don't know about you but I see that as structural rather than cyclical). And younger consumers are drinking less alcohol (or not drinking it at all). The data below is again from the UK, but the trend applies more widely ...

Since 2005, the overall amount of alcohol consumed in the UK, the proportion of people reporting drinking alcohol, and the amount of alcohol people report consuming have all fallen. This trend is especially pronounced among younger people.

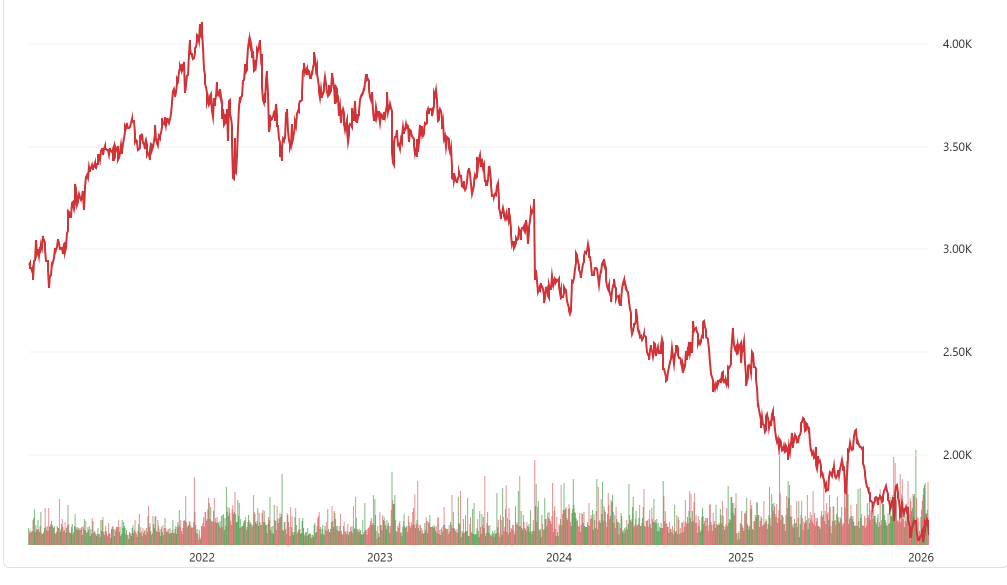

My key point is simple - long term structural declines such as these can go from being background noise to impacting a company's financial bottom line. And just to make this very real, below is the Diageo Plc share price over the last five years. Yes, I am very aware that other factors have impacted this, but ....

What can companies do?

It's arguably easier for companies exposed to meat/dairy than it is for spirits companies. Or at least it's easier for food processors and retailers. Gradually shifting to offering less meat and diary, and more plant based products (a trend that is already gaining momentum) is fairly straight forward. According to the Good Food Institute ...

The U.S. plant-based food industry has grown and evolved substantially over the past decade. When we began tracking plant-based food sales in U.S. retail, we sized the 2017 market at $3.9 billion, according to SPINS data. In 2024, the market was worth $8.1 billion.

This is now a mainstream rather than niche product category.

So, maybe one obvious question to ask of the food companies you are invested in is 'please disclose your sales of meat/dairy vs plant based'. After all, this could become a key future issue for investors.

One last thought

We should not underestimate the conflict within a company that such a shift might represent. There are some very real cultural and organisational reasons why this might not happen. Or if it does, it might not happen as fast as we would like. Or putting it in financial speak, for many companies their short-term commercial plans that aim to gain market share by offering cheaper food are prioritised over those that reduce the long term risk to the business by encouraging and supporting the consumption of healthier food.

Grant me the strength to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference. Reinhold Niebuhr - a Lutheran theologian in the early 1930's

Please read: important legal stuff. Note - this is not investment advice.