What caught our eye - three key stories (week 19, 2024)

Here are three stories that we found particularly interesting this week and why. We also give our lateral thought on each one.

Read in full by clicking on the link below.

'What caught our eye' like all of our blogs are free to read. You just need to register.

Please forward to friends, family and colleagues if you think they might find our work of value.

The refinery of the future

Refineries are important parts of the current industrial complex as they process crude oil into useful products such as fuels and feedstocks for various important chemical processes.

Of course we know that burning fossil fuels is a major contributor to man-made greenhouse gas emissions so cutting down our use of them is a positive for the environment. However, what about all of those useful chemical feedstocks that ultimately produce useful end products including plastics for us? Do we have to give those up too?

Paul Martin, a well regarded chemical process development expert, argues in a LinkedIn article that the refinery of the future will be able to still produce those useful products without the need to produce the fuels. It will require a few changes.

Firstly Paul highlights one of the big burners of fuel are the refineries themselves that need to create heat to run their various processes. Electricity can replace this. Heat pumps can effectively reuse waste heat very efficiently and in fact it is only not done more now due to the cheapness of fuels and cooling water currently, as Paul points out. In the future as externalities such as pollution get priced into fuels efficient processes will likely become the norm. Where higher temperatures are required, electric heating, including plasma arcs, can be used.

Secondly, residual 'waste products' from refining that are often burned as fuels too, need to be reconsidered and even transformed further into useful products, even if that means using inefficient processes - as Paul argues, that is still better than burning plus capturing the CO2!

Will it mean petrochemicals and plastics will be more expensive in a post-decarbonised world? Probably with the higher processing costs offsetting the cheaper feedstocks, but as Paul points out "... that's good expensive [as it] means we'll be motivated to conserve and recycle them better."

It is a very interesting and well written article - definitely worth a read.

On the same topic, an interesting paper published in Nature by Professors Bert Weckhuysen and Eelco Vogt from Utrech University examined the viability of a completely fossil-fuel free future refinery. In their future refinery, chemicals and monomers are made from biomass and plastic waste. They conclude that such a refinery whilst technically feasible and with the potential to become carbon-neutral, it would require a huge amount of green energy to produce the hydrogen required in the conversion processes.

Transitioning the chemical sector is both important, and a major challenge - technologically and financially.

Technologically because there is uncertainty around the best pathway. We have some really good pointers as to the direction of travel, but we are still a decade or more away from having the full answer.

Financially because the new pathways will require very different means of production, exposing the industry to stranded assets.

The chemical industry is fundamentally different from industries such as oil and gas. Most people do not really care if the oil and gas industry survives financially (in the very long term). They know that at some time over the next three decades other alternatives will largely replace fossil fuels. Oil and gas may survive in some form, but it will be a much smaller industry, a niche energy provider in a world of electrification.

Link to blog 👇🏾

Rioting farmers and the importance of engagement.

A Vox article caught our eye this week titled 'How rioting farmers unraveled Europe's ambitious climate plan.'

The article discusses the ongoing conflict between farmers in the European Union (EU) and the EU's efforts to implement environmental regulations through initiatives like the Green Deal and Farm to Fork strategy. Despite being a relatively small sector economically, the agricultural industry in the EU wields significant political influence due to its ability to mobilise protests and its historical status as a recipient of generous subsidies and protectionist policies.

Farmers perceive environmental regulations as a threat to their livelihoods and an overreach of government control and have staged protests across Europe involving tactics like blockading roads with tractors and dumping manure on city streets.

The author argues that the EU's long-standing policies of subsidising and protecting the agricultural industry, originally intended to ensure food security and support rural economies, have created a powerful lobby that opposes necessary reforms. The protests have effectively stalled or weakened key aspects of the Green Deal, with politicians buckling under pressure from the agricultural lobby and concerns about right-wing populist gains in upcoming elections.

The bottom line is that 'rioting farmers' have made politicians shift position. Voters matter. How different interest groups are engaged can be key to broader reforms. Interesting to note, as the author does, that the February 2021 decision to remove red meat from school menus was actually a socially distancing driven measure (prepare one hot meal that all can eat reduces people mixing). The December 2023 proposed cut to diesel subsidies in Germany were really driven by the country's budgetary crisis rather than environmental regulations.

This point got us thinking laterally to other examples such as the built environment.

The built environment is an integral part of societal existence and an important sustainability theme. As well as forward looking new construction and design, there are solutions to improve the environmental impact of existing infrastructure, through retrofitting. However, affected individuals, particularly in residential and SME, need to clearly understand all of the dynamics involved before they can make a decision to retrofit.

Language is important...

For example with home heating / cooling, if you try to persuade people to adopt new technologies with the promise that you would reduce their carbon emissions, you may get a varied response. However, if you instead promised it would reduce their cost to keep their homes at a comfortable temperature, I suspect, all things being equal, you would get consensus on that (and as an aside, we can reduce your carbon emissions).

For many, the upfront costs and disruption involved are too much of a barrier. That is where a place-based model comes into play and the resident can focus on affordably keeping their home at an appropriate comfort level with the secondary benefit that harmful emissions are also being reduced.

Something we have written about before in conjunction with LivingPlaces 👇🏾

Hemp as a transition material?

Regular readers will know that we see the built environment as one of the key areas to focus on for transitioning to a more sustainable world (just look at the previous story☝🏾 ). It is an integral part of societal existence and a major resource consumption problem (40% of global raw materials) and decarbonisation problem (as much as 40% of energy-related GHG emissions) that needs investor, government, business and consumer attention.

The materials that we choose to construct buildings with can address emissions in two ways. Firstly by reducing the amount of carbon emitted during the creation of those materials and secondly reducing operational carbon or the emissions produced from running the building - this is principally via their thermal properties in regulating temperature once installed (reducing additional heating or cooling requirements). This also reduces running costs.

We have written about alternative construction materials and in particular natural ones in the past. Timber / Wood is one such example👇🏾

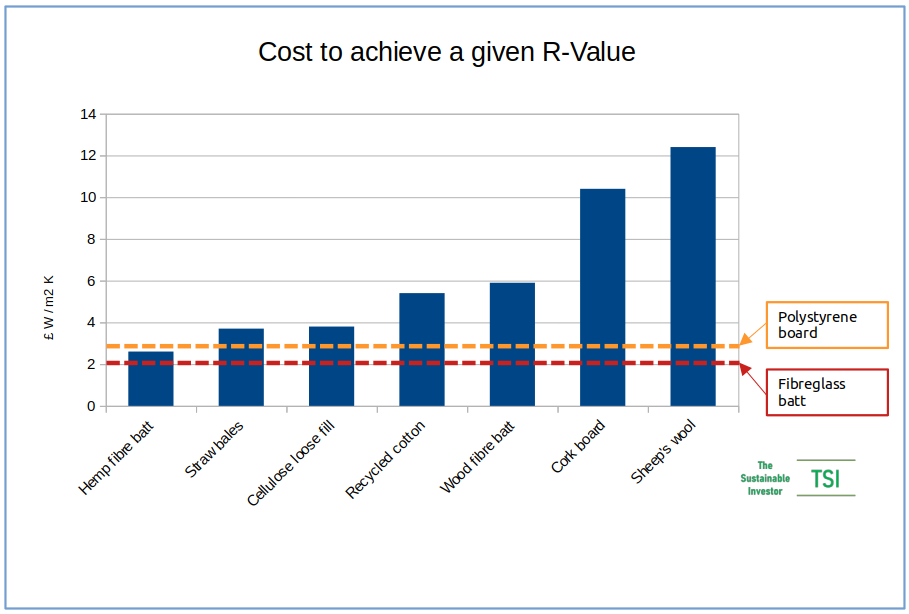

We have also previously looked at how natural materials compare as thermal insulators - spoiler alert: they compare very favourably 👇🏾

One of the materials we looked at was the subject of a recent article in The Conversation - Hemp. The author, Bernardino D'Amico from Edinburgh Napier University highlights the vital role that hemp can play. As a fast-growing plant (four metres within four months), hemp absorbs CO2 from the atmosphere more efficiently than trees during cultivation. Industrial hemp can absorb twice as much CO₂ compared to trees, with approximately one hectare of hemp estimated to sequester between eight and 22 tonnes of CO₂ in a year.

When used for long-lasting building materials like insulation or hemp-lime blocks as concrete alternatives, the absorbed carbon gets stored for an extended period, delaying its re-release into the atmosphere. D'Amico's own research into thermal insulation estimates that polyisocyanurate (a common synthetic insulating material) embodies approximately 45% more than a hemp insulation panel that transfers heat at the same rate. And it is reasonably cost effective from a thermal perspective as our own research from last year shows👇🏾

After a decline due to the rise of cotton and synthetic materials, hemp production is resurging, driven by modern processing capabilities that enable hemp to compete with polymers across applications, including construction.

Furthermore, hemp farming improves soil health, requires less water than crops like cotton, and is naturally resistant to pests, minimising pesticide use.

What we found most interesting about the article though was the point about hemp as a transition material. D'Amico doesn't profess hemp to be a permanent solution, but rather as something that buys time for developing other mitigation strategies.

This is an important aspect of sustainability thinking. Too often one hears discussion of the end point without understanding the route to get there. Transition is a series of steps. Nature, the environment and society will not wait for us to reach the end point. We need to understand what can help to begin the reductions now - to buy us time.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.