Green steel - we all want it don't we?

Green steel is clearly a good thing. But it's clearly going to need a lot of government support to get from where we are now, using a lot of coal, to where we want to be, using mostly renewables.

Summary: Government support for industries transitioning to using mostly renewables protects domestic industry and the jobs it creates. But what if, for example, green steel could be produced cheaply outside of a domestic region? If that meant putting domestic industry jobs at risk, would governments be as keen? The MENA region produced just 3% of global crude steel in 2021 but it accounted for nearly 46% (55 Mt) of the world’s Direct Reduced Iron production. Some of the largest iron ore pelletising plants in the world are in MENA too.

Why this is important: If renewable electricity becomes cheap enough, we could see green steel production potentially moving at scale to the MENA. That could be interesting politically, and it might put the current consensus around industry support at risk.

The big theme: Over the long term, the production of many industrial materials could be relocated, as companies switch from the use of fossil fuels to renewable based inputs. Historically, the decision as to where to site large production plants was based on easy access to key raw materials. That may not necessarily be the case going forwards.

The details

It's clearly going to need a lot of government support to get from where we are now, using a lot of coal, to where we want to be, using mostly renewables. While some governments might provide that support because "it's the right thing to do", for others it's about protecting their own domestic industry and the jobs it creates. The industry directly employs c. 310,000 people across the European Union, with a lot more relying indirectly on steel jobs. These are jobs that are seen as being worth protecting. Green steel is clearly a good thing, we must all agree on that.

But what if green steel could be produced cheaply outside the EU, putting the domestic industry jobs at risk. Would governments be as keen then?

At present, the main technology used to make steel is known as the BF-BOF process. Here, iron oxide is reduced to iron inside a blast furnace (the BF element) with coke (derived from coking coal) as the reducing agent. The resulting pig iron is then processed into steel in a basic oxygen furnace (the BOF element), where oxygen is blown through the molten, carbon-rich pig iron to reduce its carbon content. In 2021, 71% of global crude steel production was made this way, but it produces a lot of GHG emissions, and we mean a lot.

One technically viable solution to the green steel challenge is to shift to processing the iron ore using green hydrogen in the direct reduced iron (DRI) production process, then using electric arc furnaces (EAF), powered by renewable energies, to produce steel.

To be clear, this alternative is not yet cost competitive. To get there we will need cheap and abundant renewable electricity, both to produce green hydrogen and to power the electric arc furnaces. This is probably going to come from solar, potentially with wind and battery back up. When could we get there, best estimates suggest later this decade, so not a long time if you are currently thinking about building a new steel mill, or maybe undertaking a major refurbishment.

Why we think this analysis is interesting.

The report, from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, identifies the opportunity for the Middle East & North Africa region to become, over time, a powerhouse in green steel production. This is driven largely by the continuing industry shift from the old-style blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) technology, that uses coal to make iron, to the direct reduced iron-electric arc furnace (DRI-EAF) route. This second technology removes oxygen from the ore without melting, using a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen. This currently comes from natural gas.

The MENA region produced just 3% of global crude steel in 2021 but it accounted for nearly 46% (55 Mt) of the world’s DRI production. Furthermore, some of the largest iron ore pelletising plants in the world are in MENA and hence the supply of DR-grade pellets is not a hurdle. Initially, it would be possible to replace 30% of natural gas with hydrogen in the incumbent fleet of DR plants without any major equipment modifications. The region could then gradually move towards 100% green hydrogen to produce carbon-free steel.

Regular readers will know that we frequently consider how, over the long term, the production of many industrial materials could be relocated, as companies switch from the use of fossil fuels to renewable based inputs. Historically, the decision as to where to site large production plants was based on easy access to key raw materials. In the case of aluminum for instance, the key input is cheap and abundant electricity, which is why you find most plants in regions with hydro electricity generation.

It is estimated that the steel industry is responsible for 7% of total CO2 emissions. If global steel production were a country, it would be the third-biggest emitter in the world after China and the U.S. The likely game changer is using green hydrogen in steelmaking, a subject at the top of all recent steel decarbonisation studies.

The key raw materials could therefore change dramatically if the industry shifts to green steel. As the report highlights, this can be produced by applying green hydrogen in the direct reduced iron (DRI) production process, then using electric arc furnaces (EAF)—powered by renewable energies—to melt it. Some of the large end users of steel, such as automotive OEM’s, have plans to eliminate carbon emissions completely from their entire value chains (including their suppliers). For this to happen they need green steel to be available at scale and at an affordable cost. Which means cheaper renewable electricity.

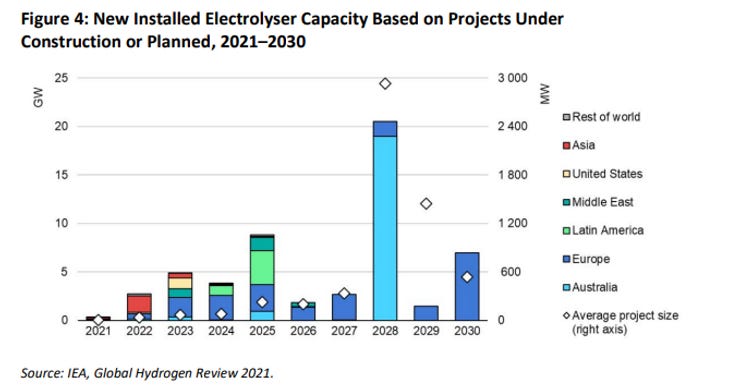

In terms of future cost, the MENA region is “blessed” with excellent solar resources, with for instance IHS Markit forecasting that by 2050 the region will have added c. 334GW of solar capacity. This can potentially power both the production of green hydrogen via electrolysis, and the electric arc furnaces. Plus, the region is already planning to start building green hydrogen electrolysers at scale (see the chart below). As the report highlights, the MENA is already the leading source of DR grade iron ore. So, potentially, all of the key inputs come together.

The problem is currently cost, green steel is still more expensive. How much more expensive is hard to know for sure. Many people quote a recent Time article, that refers to climate think tank RMI saying its 25% more expensive. But following the source, in a 2020 article RMI stated that “with power prices at $25 per megawatt-hour, and hydrogen electrolyzer costs of $450 per kilowatt, zero-carbon primary steel without coking coal can reach a fully loaded production cost of $400/ton. This is competitive with many existing steel mills today.” The bottom line is that for cheaper green steel to be available at scale, we need cheaper renewable electricity.

If that happens, we could see green steel production potentially moving at scale to the MENA. That could be interesting politically, and it might put the current consensus around industry support at risk. Yes, there are a few "ifs" in this analysis, and there are some material cost barriers to overcome. But it's something to bear in mind and definitely something to take account of in our longer-term investment scenarios.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.