Do investors use the wrong models, indices and decarbonisation, and chicken and egg of green steel

Are investors using the wrong models?

What mid term scenario about our environment do you use in thinking about your investments? If you are like most investors, you use one of the available economic models. Are they really consistent with the science? What if they are massively under estimating the risks to your investment portfolios?

Recent research from the University of Exeter and the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries suggests that many investors are using models that are totally inconsistent with the known (and agreed) science. So, what is the problem?

Some economists have predicted that damages from global warming will be as low as 2% of global economic production for a 3°C rise in global average surface temperature. Such low estimates of economic damages – combined with assumptions that human economic productivity will be an order of magnitude higher than today – contrast strongly with predictions made by scientists of significantly reduced human habitability from climate change.

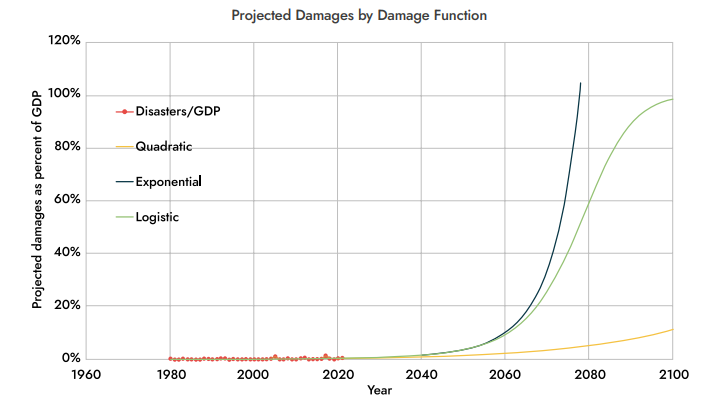

How can we have such a massive difference? The answer is ‘easy’. Economists seem to argue that the future will look like the past, which leads them to what is known as a quadratic relationship - greater warming leads to more economic damage, but at a steady non-accelerating relationship. This is the lower yellow line in the chart below:

By contrast, most scientists think of a world of accelerating damage and tipping points. This gives the exponential or logistic plot in the chart.

The difference between the two approaches might seem small when the temperature increase is small, but these differences become massive as the world warms up. When you add in the fact that most economic models only look at temperature, not rainfall etc, you can see why there is such a big difference.

If you were looking after the assets of a pension fund, which scenario would you find most likely?

One of the bigger UK pension funds, the £90bn (€104bn) USS fund is working with academics at the University of Exeter to establish an “approach to climate scenario analysis that integrates a deep understanding of climate science with its interaction with macroeconomic and financial markets outcomes over different time horizons,”

In other words, the very question we posed. If the science says that climate change etc will cause material damage to our environment, then how can economists argue that the impact on our economy will be small? Someone must be wrong, and it’s probably the economists.

Do indices actually contribute to decarbonisation?

Lots of investors (allocating billions of dollars of capital) use sustainable financial indices, either via passive ETF-type products, or as benchmarks for more active products. They do this because they believe that investing 'in these indices' will actually advance decarbonisation (or any other of the sustainability aims such as biodiversity).

Do the indices actually contribute to decarbonisation and the transition to net zero, or do they just encourage the perception of change, while not really making much difference on the ground?

This video was a panel discussion at the recent Oxford Sustainable Finance Summit 2023. The topic of sustainable indices might sound arcane and boring, but it's really important. The key question is ... does the capital allocated against these indices actually make a difference?

Panellist Ellen Quigley is, in our view, one of the best thinkers on this topic. She expounds on the important difference between the impact of equity vs debt really well (starting at around 30 minutes in). If you invest using a sustainable equity index, and you don't actively engage and vote (and most passive investors do not), then you are probably not making much real difference on the ground. Why? Largely because public equity is mostly a secondary market. We buy and sell shares among other investors. Most companies don't raise new equity. So while they care about their share price for other reasons, it has little impact on their real world financing decisions.

However, they do frequently raise debt and refinance existing debt, which means that they need easy access to the debt markets. So, if you exclude companies who are carrying out unsustainable activities from your debt index, then you are reducing the pool of available capital. There is some evidence that this makes the cost of debt for the excluded companies higher. Which makes them, at the margin, less likely to fund 'dirty' projects, and more likely to fund 'green' projects.

In an age when the use of passives and indices is increasing, we need to think more deeply about what this means for our efforts to make the sustainability transitions actually happen. If you use passive equity, you have to make sure your asset manager is engaging and voting in a manner that is aligned with your views, and if you use debt then exclude funding activities you do not support. These are decisions you should not outsource.

One final point from Ellen (around 40 mins in) is really valid: decarbonising investment portfolios is unlikely to decarbonise the real world.

We discuss the concept of 'universal owners' in a Sunday Brunch. Universal owners are savers (i.e. investors) who hold broadly diversified portfolios. Describing this in financial terms, they are unable to avoid/diversify away these external costs on society, and so regardless of how good their asset managers might be at beating the index, their long term financial returns are diminished. Universal owners need to think about their investments differently, in a way that is alien to how most asset managers currently work. Change is coming.

Link to blog 👇🏾

The chicken and egg of green steel.

'Chicken and egg' is a popular analogy in sustainability transitions. How do you get companies to invest in new ways of doing things, when the end demand doesn’t exist yet? How do you get companies to buy new products, when no one is making them yet?

Green steel is a great example of this. It’s currently more expensive to produce than traditional steel, for what is the same product, just with lower carbon emissions. What breaks this log jam?

The RMI believe they have found the key. US companies which purchase steel are sending a strong, clear demand signal for near-zero emissions steel, which can now be competitively met with US supply due to the federal incentives kick-starting a new low-emission marketplace.

US annual demand for near-zero emissions steel is anticipated to reach 6.7 million tons (Mt) by 2030. To put this in context, the United States produced approximately 82 Mt of steel in 2022, with a typical steel plant producing 2 million tons per year. Since not one ton of US steel currently produced is near-zero emissions, American steelmakers are at a critical investment juncture: build near-zero emissions steel plants now or miss the boat by forcing US companies to import to meet their near-zero emissions steel needs.

Who wants to buy this green steel? One big customer group is automotive, at roughly half of the expected 2030 demand. Then it’s buildings, followed by machinery and appliances.

Is this finally an industry at the tipping point, where the chicken and egg debate is resolved?

Not only is green steel an important sector from a GHG emissions perspective, it could be the trail blazer for a number of other important transitions. Here is a Deep Dive on that.

Link to blog 👇🏾

Please read: important legal stuff.