What caught our eye - three key stories (week 17, 2024)

EV special : is this going to be the decade of the cheaper Chinese EV, the need for fast charging, and battery technology is changing.

Here are three stories that we found particularly interesting this week and why. We also give our lateral thought on each one.

This week we are trying something a bit different. We are going to focus on three aspects of just one story.

Earlier in the week the IEA published their 2024 Global EV outlook. This is a significant story for two reasons.

First, transport is a really important sector for decarbonisation. According to Our World in Data, transport accounts for around 20% of global CO2 emissions, with c. 75% coming from ground transport. So, a good problem to solve.

And second, its importance comes from the fact that we have a solution that reduces transport emissions, one that we know works. Along with decarbonization of our electricity network, transport is the most investible 'green' theme.

That solution is obviously Electric Vehicles. We can build them at scale, they are getting cheaper, and, assuming we decarbonise electricity generation, they can make a real difference. But, it can be complicated.

We are sure you will have seen a lot of coverage of the report. So, rather than rehash a summary, we have picked three aspects where we think a bit of thought is needed.

These are - how do we expand EVs outside of the current three big markets - is this the decade of the Chinese mass market EV, what is happening on EV charging, and advances in battery technology. What links them all, as with most things to do with EVs, is China.

Let us know what you think ...will EVs make the global jump to the mass market, as they have already done in China, or will they struggle to gain more traction. We think the former.

Read in full by clicking on the link below.

'What caught our eye' like all of our blogs are free to read. You just need to register.

Please forward to friends, family and colleagues if you think they might find our work of value.

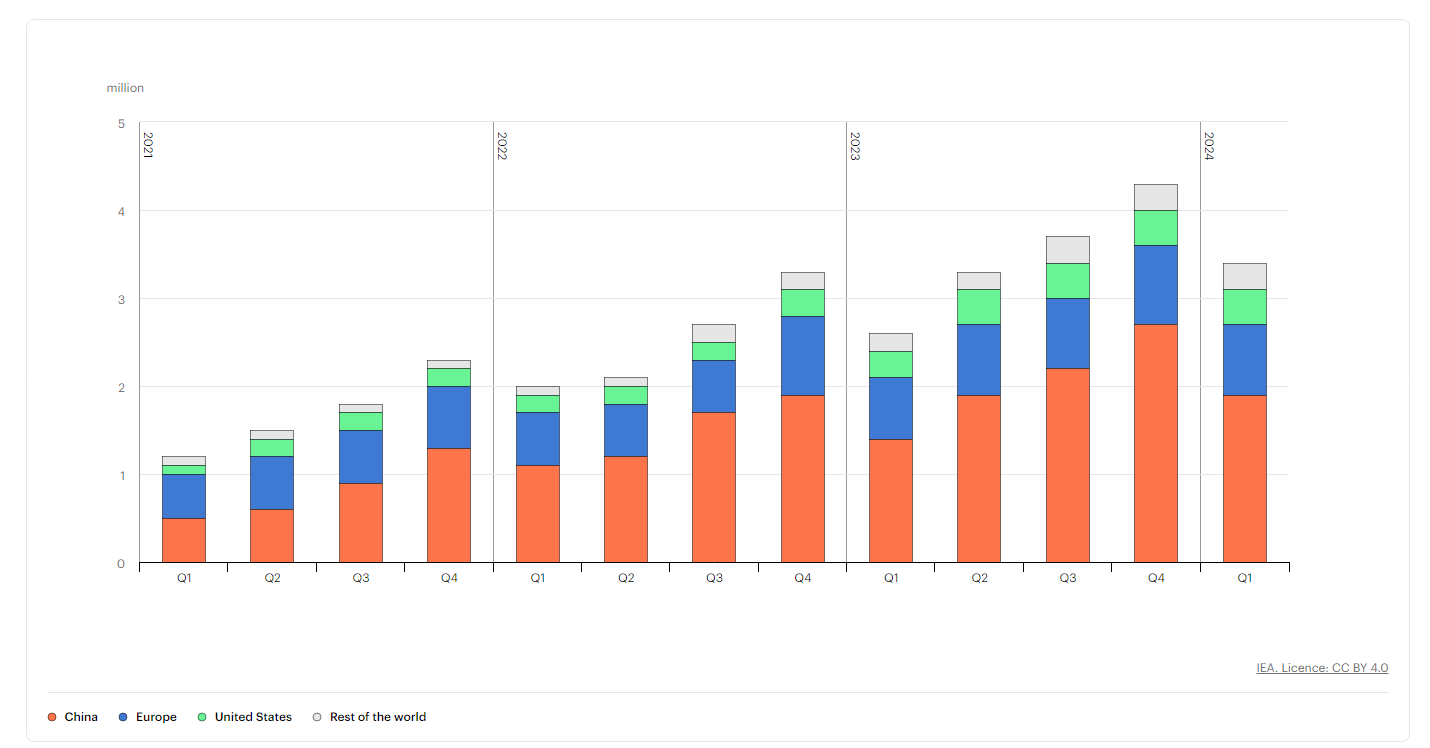

EV sales growing - but where matters

Topic 1: Is this going to be the decade of the cheaper Chinese EV? And what might this mean for the market share and profitability of European and US OEMs?

The IEA report sets out the case for EV optimism. "Electric car sales could reach around 17 million in 2024, accounting for more than one in five cars sold worldwide. While tight margins, volatile battery metal prices, high inflation, and the phase-out of purchase incentives in some countries have sparked concerns about the industry’s pace of growth, but global sales remain strong."

In the first quarter of 2024, electric car sales grew by around 25% compared with the first quarter of 2023, similar to the year-on-year growth seen in the same period in 2022.

In 2024, the market share of electric cars could reach up to 45% in China, 25% in Europe and over 11% in the United States.

Most of the coverage we have read takes the line that 'despite challenges EV sales continue to grow at what is an astonishing rate'. And this is true. As the IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol said in the launch video ' despite the headwinds EV sales have done much better than many pessimists expected'.

But! Lets look at the data in a slightly different way. The vast majority of EV sales in 2023 were in China (60%), Europe (25%) and the United States (10%). Together 95% of all global EV sales took place in those three markets. And yet together they only made up 65% of total car sales. What is happening elsewhere?

The short answer is other than pockets of positive news, EV market penetration outside of the big three regions remains weak. Many analysts highlight price, with EV's being too expensive for many consumers. But this misses two important aspects.

The first is the question - are we building the 'wrong' types of EVs? As the report points out, in 2023, two-thirds of available electric models globally were large cars, pick-up trucks or sports utility vehicles. These are not the cars that most global consumers want.

And then we have China. Our second point. The IEA estimates that more than 60% of electric cars sold in 2023 were already cheaper than their average combustion engine equivalent.

This is worth repeating. In a world we we think of EVs as being expensive, nearly 2/3 of EVs in China were cheaper. Given this, is it any wonder that the IEA estimates that by 2030, nearly 1/3 of cars on the road in China will be electric. Not new vehicles sold, vehicles actually being driven around.

Yes, there are some signs that other car OEMs are focusing more on cheaper EVs. But, again quoting the IEA report - only 25% of the 400+ launches expected over the 2024-2028 period are small and medium models, which represents a smaller share of available models than in 2023.

And, can a $25,000 'cheaper' EV really compete with the mass market offering coming out of China, where local carmakers already market nearly 50 small, affordable electric car models, many of which are priced under $15,000.

I am old enough to remember how first Japanese and then Korean automotive brands reshaped the car industry. After doing the same in motorbikes.

So a useful question to ponder is - are we heading for a world where European and US automakers hold on to EV market share in premium, but lose out badly in the mass market? And what might this mean for economics and jobs?

And as you ponder this ... remember that EVs are not just about cars. Two and Three wheelers matter as well. Something we wrote about back in 2022.

Link to blog 👇🏾

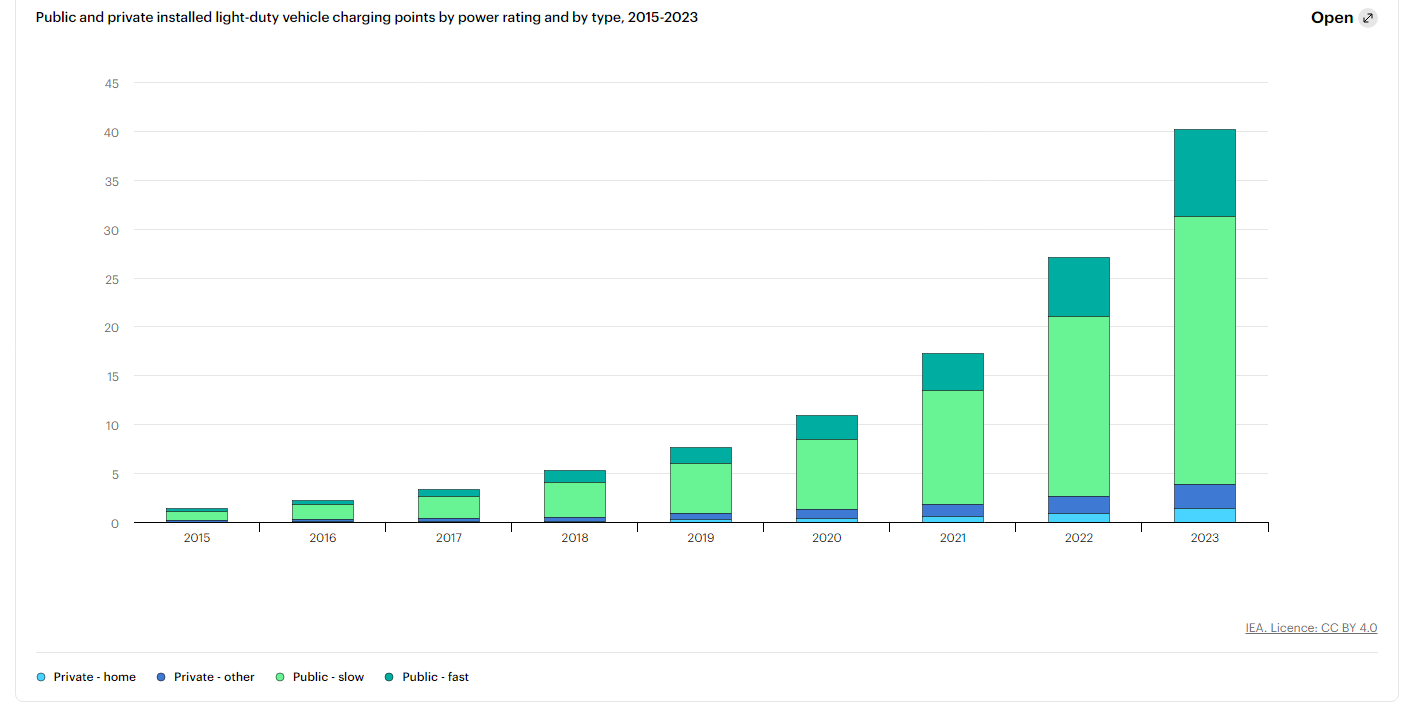

How important are public chargers?

Topic 2: If cheaper EVs start to become the norm soon, will the absence of fast public EV chargers hold back adoption? The answer in many markets is probably yes, but it doesn't have to be that way.

In topic 1 we talked about the growing importance of cheaper EVs. In topic 2 we think some more about one of the possible barriers to mass market adaption - charging.

According to the IEA report, the global number of installed public charging points was up 40% in 2023 relative to 2022. And growth for fast chargers outpaced that of slower ones. As they say:

In major EV markets, the deployment of charging points is continuing apace thanks to targeted policies. Broad, affordable access to public charging infrastructure will be needed for a mass-market switch to electric transport and to enable longer journeys – even if most charging continues to take place privately in residential and workplace settings.

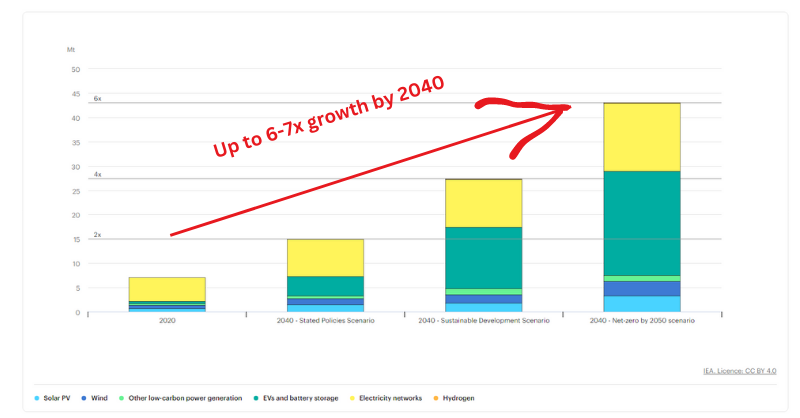

To reach EV deployment levels in the IEA Announced Policies Scenario, public charging needs to increase sixfold by 2035.

The good news is that the pace of installation of public EV chargers is growing, up 40% (the top two colors in the chart below). And an increasing percentage are fast chargers, up 55% (the very top color). This is important because for many drivers, charging on the go needs to be quick. If you are driving for work, or travelling a long distance for a holiday, you don't want to be sitting around for hours as your car charges back up.

For most people the number of fast public chargers is important. It might not be rational, after all the vast majority of our journeys are short, and most are either to or from our home.

So, if you can have an 'at home' slow charger (preferably a smart one), then you will only use public fast chargers very occasionally. But, for the odd occasions you will need one, they are important. Very few people I know would take an EV on holiday, if fast chargers were not available.

So, if most people will charge at home, and if public fast chargers are something most of us will only use occasionally, what does this mean for who pays for them?

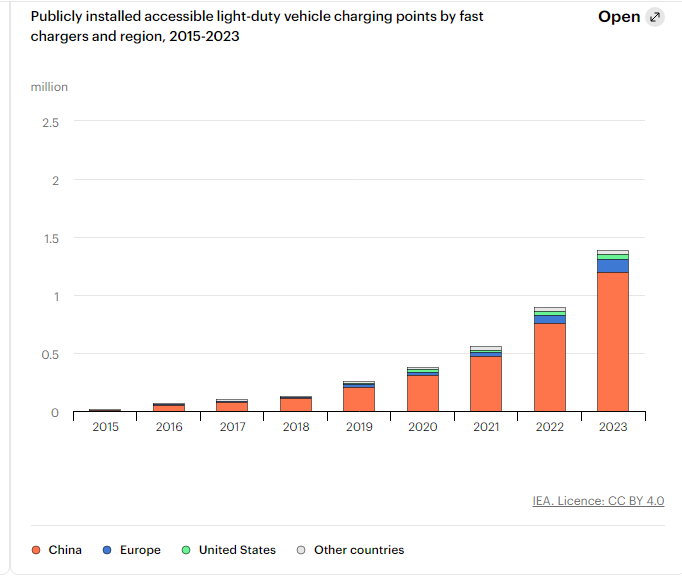

If we look at China, you can see this already happening. They had a 2025 policy ambition of EV car sales share above 35%. Which they have already achieved! And they are now shifting focus to charging infrastructure development, targeting full coverage in cities and on highways by 2030, as well as expanded rural coverage.

And this is likely to further open up the gap (in fast public charging) between China and the rest of the world. China is the orange portion of the bars!

But remember, the stand alone economics of public fast chargers at scale could be problematic. If we only have a few of them, located in areas of high demand, their utilisation is probably going to be enough for them to fully pay their way. Even at lower EV market share levels. But as we get more of them in less popular areas, the economics gets tougher. And yet we need them pretty much everywhere if EVs are going to become the mass market product that societies and governments hope for.

This is fine if you are China. But what about the rest of us?

The mix of fast public and private/at work chargers is something we need to think about. And given that some countries are already approaching the innovation S curve shift into the mass market, we need to think about it soon. It's a topic we wrote about back in March 2023.

Link to blog 👇🏾

Where we end up with battery technology matters.

Topic 3: Can we produce enough batteries to met EV demand?

In topic 2 we talked about one barrier to mass market adoption of EVs - charging. That is largely a solvable challenge, if we have the political will and some investment support. The battery challenge is more difficult. We have highlighted in the past the need for more mining of what are known as critical minerals. Much more mining. But even here solutions exist, if we can get around the politics.

The IEA report sets out in a bit more detail the scale of the challenge.

The growth in EV sales is pushing up demand for batteries, continuing the upward trend of recent years. Demand for EV batteries reached more than 750 GWh in 2023, up 40% relative to 2022.

95% of the growth in battery demand related to EVs was a result of higher EV sales, while about 5% came from larger average battery size due to the increasing share of SUVs within electric car sales.

More batteries means more of some types of mining

More batteries means extracting and refining greater quantities of critical raw materials, particularly lithium, nickel and maybe cobalt.

Rising EV battery demand is the greatest contributor to increasing demand for critical metals like lithium and cobalt. Battery demand for lithium stood at around 140 kt in 2023, up more than 30% compared to 2022; for cobalt, demand for batteries was up 15% at 150 kt. EVs are important for these minerals, as they make up the majority of the current demand (85% and 70% respectively).

It's also similar, although to a lesser extent, in nickel. Battery demand for nickel stood at almost 370 kt in 2023, up nearly 30% compared to 2022. But batteries only make up 10% of total nickel demand.

Do we have enough battery production capacity? Yes

Interestingly, the future challenge is less about having enough battery production capacity. At least it is if we exclude politics.

Part of the reason is China. As the IEA highlights - in 2023 China used less than 40% of its maximum cell output. And cathode and anode installed manufacturing capacity was almost 4 and 9 times greater than global EV cell demand in 2023. They are making way more battery material than they need now, so it's no surprise that they are big exporters.

This imbalance is changing. In 2023, the installed battery cell manufacturing capacity was up by more than 45% in the United States, and by nearly 25% in Europe. If current trends continue by the end of 2024, capacity in the United States will be greater than in Europe.

And we might need less cobalt than we previously thought.

Cobalt is controversial. Much of it comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo, where human rights are an issue. It's a topic that comes up a lot. Critics of EVs say how can EVs be clean, when producing them involves human rights abuses. And sustainability professionals worry about how do you fix this?

Part of the answer is battery chemistry. Despite what you might have read, not all batteries contain cobalt. There is a battery type that uses no cobalt. It's called LFP (it stands for Lithium Iron Phosphate - the F is from the chemical symbol for iron - Fe).

Over the last five years, LFP has moved from a minor share to the rising star of the battery industry, supplying more than 40% of EV demand globally in 2023, more than double the share recorded in 2020. And some analysts expect it to be over 50% of demand very soon.

Why? because it's cheaper. Which is probably why LFP production and adoption is primarily located in China, where two-thirds of EV sales used this chemistry.

And looking further out, there could be a future for sodium-ion batteries. These batteries not only don't use cobalt, they don't use lithium either. The IEA estimates that sodium-ion batteries could be 20% cheaper, and so they could become the battery of choice for smaller urban EV's. It will not surprise you that the announced sodium-ion manufacturing capacity in China is estimated to be about ten times higher than in the rest of the world combined.

The other aspect that we need to think about is battery recycling, what some people call 'urban mining'. This could also help bridge some of the critical mineral gap.

Link to blog 👇🏾

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.